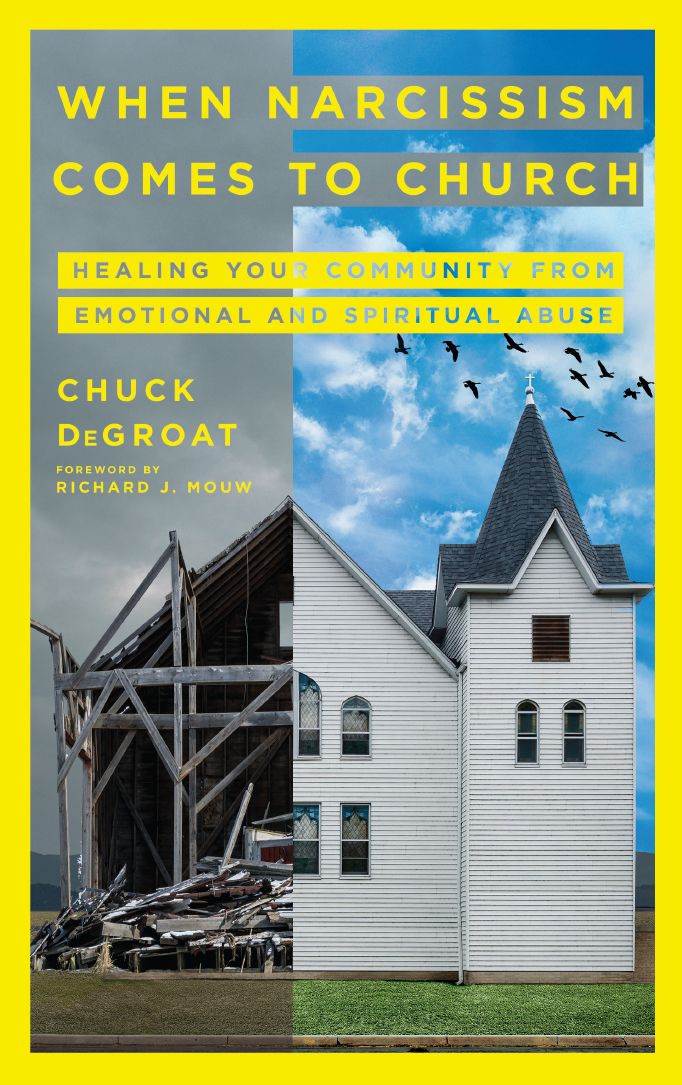

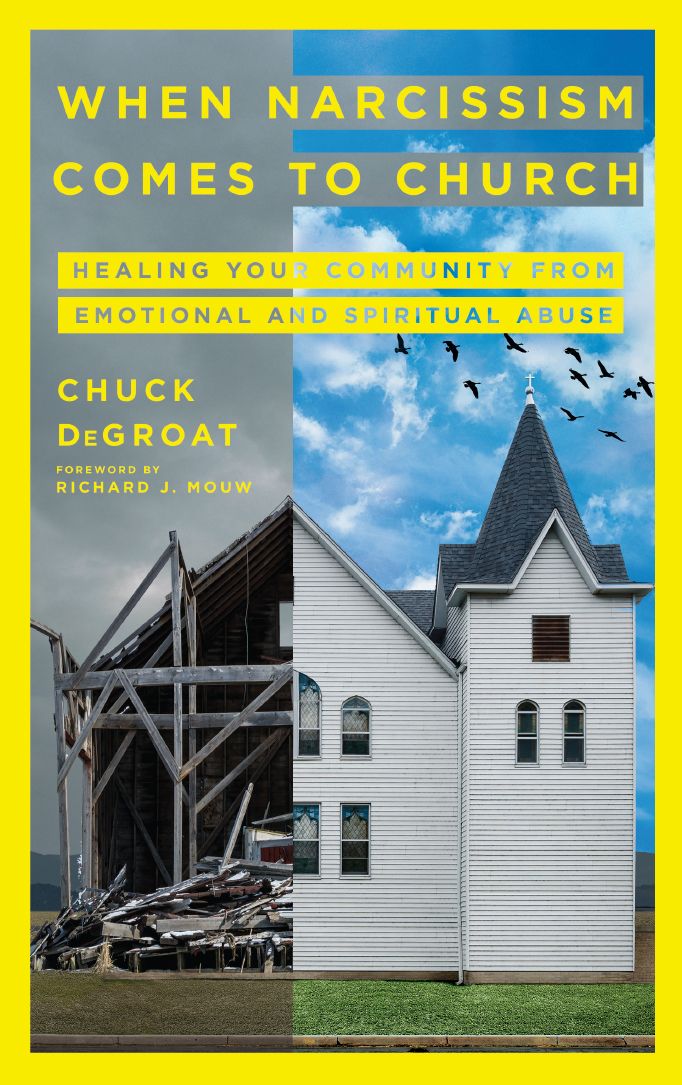

When Narcissism Comes to Church by Chuck DeGroat – A Review

I can’t even remember the last time I posted a book review on here. Despite the assumptions we might make about lockdown, I’ve found it very unfruitful when it comes to reading books! As such a little pile of half-plundered books that I want to read and share has slowly grown on my desk. I first dipped into When Narcissism Comes to Church a while back, and finally got the opportunity to dive in deeply more recently. In some ways these reviews is for my own sake, an opportunity to note key lessons and quotations that I want to hold onto. I hope the question format makes it more accessible, despite the length.

The Book in a Nutshell?

Make no mistake, When Narcissism Comes To Church is likely to be painful read. The book is jam-packed with examples; gut-wrenching, church-shaking anecdotes of individuals in ministry, or whole church structures, where narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) has set-in. These come from twenty years of DeGroat observing and counselling in an area that he believes is largely under-explored in church circles. It is the church’s ‘dirty little secret’; ‘ministry is a magnet for a narcissistic personality’.

As such, WNCTC is uncomfortable. It calls us to ask some hard questions of our ministry practices. Do we overlook someone’s narcissistic behaviour (e.g. arrogance, rumours of bullying, over-control) because we want their ‘powerful sermons, persistent success and perceived authority’? Do we overplay vision and ‘theology’, whilst ignoring character? Do the warning lights of ‘inconsistencies and minor relational violations’ get ignored because ‘we couldn’t imagine him/her doing something like that’?

What is Narcissism?

Often we might think of narcissism as simply self-obsession or grandiosity. Those are certainly key traits, but DeGroat explores the cause, as well as the manifestation. For example, the myth of Narcissus is often told as a tale of excessive self-love, but Terrence Real has argued that Narcissus suffered more from a deficiency of self-love. He is dependent upon his image, believing that only this can bring him life in the face of his wounds and struggles. That’s why DeGroat prefers Christopher Lasch’s definition of narcissism: ‘the longing to be freed from longing‘. That is, narcissism occurs as an individual struggles to tolerate their own limitations and fragility.

The theory is that rather than confronting our true selves, we instead create a false self, which in turn hardens so that we lose all sense of who we truly are. We love the image of who we are, but not the ‘real self’, which we evade, as James Masterson puts it. Consequently, we use up our lives in the desire for pleasure, power, honour, experiences, in order to clothe our false selves, to ‘make myself perceptible to myself and to the world’ (Thomas Merton). The energy that is exerted into this ‘mission’ is then often channelled into rage or threat towards any who challenge the persona we seek to project. Ultimately our identity is bound-up with shifting external realities, such as the approval of others.

DeGroat is careful to say that whilst ‘we’re all susceptible to narcissistic behaviour’, NPD is something ‘far more serious, characterised by grandiosity, entitlement, a need for admiration, and a lack of empathy’. For him, intent and impact are key factors for discernment: ‘a good pastor will make mistakes – and then own those mistakes … with sincere repentance and with a real curiosity for how she’s hurt others‘. As such DeGroat imagines a scale, from a narcissistic style, elevating to a narcissistic type, elevating to a narcissistic pathology. It is the latter that is diagnosable and ‘often toxic in relationships and the workplace’. The false self becomes the ‘primary mask the narcissist wears in the world’. I was left pondering the question of intent: after all, the heart is deceptive above all things. If a narcissist isn’t aware of what they’re doing (blind self/undiscovered self), then one’s intent will presumably be murky waters.

Interestingly DeGroat also speaks of a ‘healthy narcissism’, where there is a recognition of limitations and a humble acknowledge that ‘we’re not the centre of the world’. Here is confidence rather than certainty, curiosity rather than defensiveness, empathy rather than ingratiation. It may have just been me, but I wasn’t quite clear in what sense this could still be validly described as narcissism if it’s not a false self.

Who wrote the book?

Chuck DeGroat has been counselling pastors with Narcissistic Personality Disorder, as well as those wounded by narcissistic leaders and systems, for over twenty years. He serves as Professor of Counseling and Christian Spirituality at Western Theological Seminary in Michigan, USA, has been involved in vocational church ministry and is a licensed therapist and spiritual director. WNCTC is his fourth book.

He’s therefore not lacking in experience about his subject matter – and there’s evidently a passion to call us to be alert to a danger we’ve closed our eyes to. As much as DeGroat challenges, I appreciated his posture throughout. Early on he points out that ‘when we diagnose, we are describing a pattern … never a person. All people are unique. Labels, however well intended, cannot do justice to human complexity.’ He also honestly describes confronting his ‘own latent narcissism’.

Why should I read the book?

Ultimately because, as DeGroat says, ‘we swim in the cultural waters of narcissism, and churches are not immune’. In other words, ‘it’s an us problem, not a them problem’.

Here are a few particular things I appreciated:

- DeGroat goes deeper into narcissism than the cultural soundbite. Theologically, narcissism is a ‘refusal to live within God-ordained limitations of creaturely existence’. Ironically our desire to be superhuman makes us less human. I especially valued the exploration on the impact of shame, which DeGroat calls ‘jet fuel’ for narcissists. He argues that often those with NPD are ‘living from a compensatory part of themselves that shields them from the shame and pain within’. Shame is a ‘mammoth iceberg’ below the surface. Indeed DeGroat suggests the ‘lie of toxic shame’ had a part to play in the fall in Genesis 3, as humanity believed ‘that it’s not enough, they’re not enough’ and God isn’t good to them.

- This reflection on shame is perceptive. Whilst the West is sometimes described as a ‘shameless culture’, DeGroat argues that we both suppress shame and have a decreased threshold for experiencing it. Because of this, we just don’t know how to handle inner emptiness or sadness: ‘We’re out of touch with ourselves, our hearts, our story, our feelings. We walk the earth using others and using things to satisfy the deep ache within.’

- I found DeGroat’s chapter of the ‘inner life of a narcissistic pastor’ very helpful. I vividly remember in one of my first sessions at theological college we were encouraged to value self-awareness. I remember this standing out as something that hadn’t really been underlined to me before. DeGroat develops Carl Jung’s idea of the ‘shadow self’ to capture the sense of hidden shame, secret motivations, fierce passions and burdening fears that lurk within. Robert Bly describes this as our ‘long, invisible bag’ that we all drag behind us. DeGroat argues that often narcissists are most threatened by what is within. They may be living a ‘quadruple life’: presenting a ‘public self’ to the world; a ‘private self’ to a select few; a ‘blind self’ that is observed by others but not themselves, and an ‘undiscovered self’, with unseen and unconscious aspects. He describes ‘keeping watch’. This isn’t about being paranoid or suspecting everyone, but about not dismissing warning sights, or minimising inconsistencies and relational violations.

- DeGroat also gives a chapter to exploring ‘narcissistic systems’. Like a sepsis, the impact of narcissism goes much deeper than we know. It can be a systemic infection that will leave its mark on structures, relationships and general culture. Such ‘collective narcissism’ often sees structure, shame and control used to keep an unhealthy system running. Classic symptoms include the demand for loyalty, the limitation of feedback, and shame for those who challenge/question the norm. Often distance is needed for any systemic change: we need to ‘go to the balcony’, before we can really see what’s happening ‘on the dance floor’.

- ‘The Gaslight Is On’, the chapter on spiritual and emotional abuse, is especially uncomfortable. Here DeGroat reflects on the physical wound of trauma caused by narcissism. This is not to be underestimated and yet is often is left to destroy silently, as recent scandals and reports have shown.

- One of the perceptive points DeGroat makes about evangelical culture is that whenever we identify an ‘outside enemy’ or a ‘grandiose mission’ it can lead to unhealthy victim-martyr-hero identities. Likewise, we need to be careful whenever we directly tie our plans and decisions to God’s work. If we have a high view of preaching (as I do), how do we model humility and make space for correction or challenge? Another very interesting question DeGroat raises is whether the ‘missional fervour and rise in church planting we’ve witnessed since the 1980s can be correlated with the growing prevalence of narcissism’. This isn’t about pouring water on evangelistic zeal or fervour for the Lord, but it is about acknowledging how easy it can for leaders and ministries to become unchallengeable. I wonder too if we need a bit more of Luther’s theology of the cross, rather than a theology of glory.

- A chapter on the healing process is practical, realistic and hopeful. He believes the two most important components of healing trauma are ‘awareness and intentionality’. This means bringing emotions out of the shadows and confronting reality. Some may struggle with this focus on emotions and connecting them to our history, but DeGroat is convinced we need to see how we’re formed by our pasts.

- The final chapter, ‘Transformation for Narcissists (Is Possible)’, brought the book to a powerful close. Here DeGroat is honest about his own struggles, including as a counsellor, and with them the temptation to reduce human complexity to labels and definitions: ‘So each time I sit with someone who is a narcissist, I confess. I remind myself that she is one who has hurt others deeply and one who is created in God’s image. I confess my need to define and control, and I ask for eyes and ears to heart a story much larger and to believe a redemption far greater’. Using the language of ‘splitting’, he argues that a healthy person is simply one that is aware of their complexity – and can ‘hold the good, the bad, and the ugly before God in a posture of humble surrender, grief, and repentance.’ DeGroat also testifies to his own ‘slow reveal’, opening up to his own inner complexity. This nuance was a refreshing end to the book, but perhaps still raised questions for me as to how we then discern the ‘true self’, which was the language of much of the book.

What’s the Deal with Enneagram?

DeGroat uses the Enneagram to frame some of his reflections on narcissism. If you’re unfamiliar with it, the Enneagram plots an individual against nine different personality styles (‘ennea’ being Greek for nine), each representing where we tend to gravitate in order to cope and feel safe. An Appendix takes more time to map out how narcissism shows itself in each of these styles, highlighting that whilst there are essential features of NPD, there is a ‘variance of experience best imagined through multiple lenses’.

Enneagram is an area of some controversy amongst Christians. Joe Carter did a FAQ piece on ‘What Christians Should Know About the Enneagram‘ over at the TGC blog, which offers a basic introduction. However DeGroat has responded to that piece here, saying he’s concerned it doesn’t appreciate “the enormous significance of the Enneagram as a way of understanding sin and the deeper motivations which drive us to disordered desires.” For him, Enneagram is less about labelling a personality, and more about understanding our story: “a proper and wise use of the Enneagram opens us up to a larger conversation about how our family-of-origin, our relational and cultural contexts contribute to ways of coping, often sinfully and maladaptively, in a broken world.”

My sense is that the Enneagram is a tool, and needs to be used and seen through biblical lenses. And yet such tools can offer a glimpse into our inner motivations and disordered desires.

How much is the book & how big is it?

WNCTC is 170 pages, excluding appendixes. It comes as a striking yellow-covered, slim hardback and you can pick it up in the UK for around £12.

Who will benefit from this book?

I’d especially commend this book to those involved in Christian leadership, whether full-time or not, lay or ordained. For those of us in pastoral ministry in the West in 2020, it is so easy to become ‘obsessively preoccupied with reputation, influence, success…’. We often favour the confident, compelling and seemingly strategic, perhaps baptising their ministries as ‘blessed’, ‘anointed’, ‘special’, etc, making it very hard to challenge.

For an evangelical culture facing up to scandal, emotional and spiritual abuse, and unbecoming behaviour, taking DeGroat’s challenge to heart will therefore be painful. It will mean ‘dying to illusion, to control, and to fear’ – but coming alive ‘to vulnerability, to creativity, and to connection’. But as DeGroat says, ‘only the one who allows God to expose the darkness and the light will experience the king’s compassion and healing presence.’

–

If you’re in the UK, the cheapest and most accessible place to pick up the book may be at Blackwell’s here.

Disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from the publisher, but I hope this is still a fair and honest review.